When it comes to effective interventions, writes Natalie O’Brien, a SENDCo in Birmingham, it is essential to value expertise wherever it is found – even if that means challenging traditional perceptions of hierarchy…

As SENDCo of The Oaklands Primary School, a two-form-entry primary school in Birmingham, I undertook a detailed case study last autumn to investigate the effectiveness of collaboration between a speech and language therapist (SaLT) and a teaching assistant (TA) in the context of a one-to-one speech and language intervention.

Specialist interventions do need to be guided by specialists with expert knowledge. But the focus of specialists must be to empower TAs and to recognise that they are likely to have different expert knowledge.

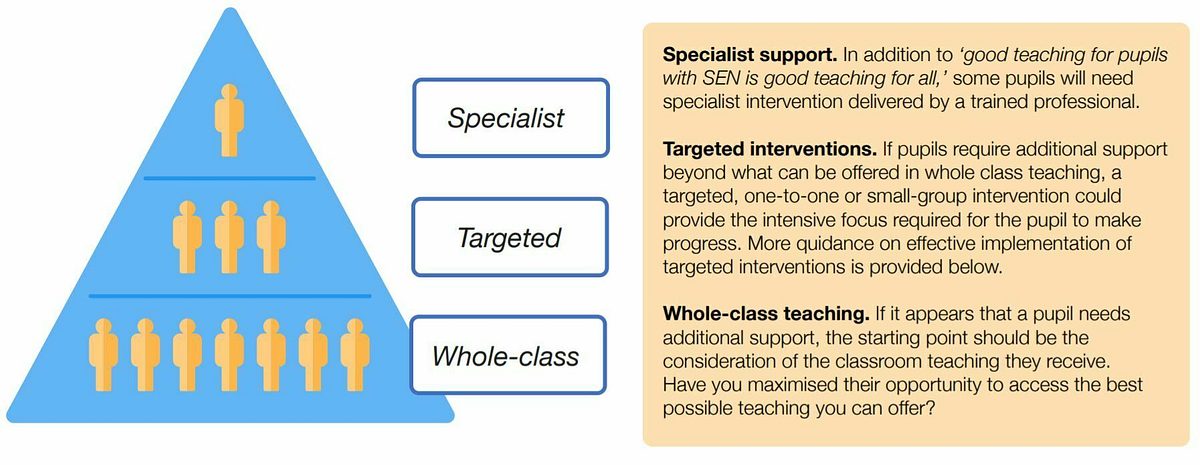

It feels like the right time to share the findings, while schools assess targeted academic support as a second tier to their school planning this year, in the light of EEF’s School Planning Guide for 2020 – 21: ‘Generally, the use of TAs to deliver high quality interventions, which complement the work of the teacher, is a ‘best bet’ and could be a powerful way of mitigating any impacts of time away from school and see positive gains for pupils.’

Nevertheless, ‘Small-group and one-to-one interventions … must be used carefully. Ineffective use of interventions can create a barrier to the inclusion of pupils with SEN.’ (EEF guidance report, Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools – recommendation 4)

Context

This was a specialist intervention, to be provided on top of excellent whole-class teaching.

It was to be guided by a SaLT and delivered by a skilled TA, who already had a strong relationship with the child and experience of delivering speech and language interventions. The SaLT was new to the school, relatively inexperienced, but highly trained

The intervention represented a significant expenditure on the part of the school. For the sake of the child, I needed to be sure that this specialist, high-cost intervention was also high value.

Findings

Difficulties appeared at the planning stage. While there was limited communication, an imbalance of power meant that this was not reciprocal. It appeared to confirm Mackenzie’s (2011:65) view that TAs are ‘often excluded from discussions about the children whom they have expert knowledge’. The planning process preferred the expert knowledge of the SaLT over that of the TA with the result that the TA was disempowered.

During the delivery phase, the power of the TA rose in importance relative to the SaLT, but, by then, their mutual understanding of each other’s roles had diverged. The SaLT defined the collaboration as ‘Working together as a team with a goal in mind; coming together holistically to benefit the child first and foremost’. The TA’s definition focused on the process: ‘Sitting down, talking and unpicking and changing’. Qualitative data demonstrated that this didn’t happen, so lack of communication created a further barrier.

A number of factors contributed to this:

- the SaLT’s assumptions and lack of experience;

- the TA’s lack of confidence in voicing her opinion, compounded by her feeling of disempowerment;

- the logistical issue of time and availability for both stakeholders to meet; and

- the SENCo’s failure to establish roles and clearly define expectations from the start.

All these factors are familiar in schools.

A way forward

To inform a positive way forward, I turned to research

Coleman suggests a move away from hierarchical structures could enable a way of working which was more inclusive and democratic (Coleman, 2011)

The work of Cheminais proposes a new leadership model – in her Handbook for SENCos she recommends that those with ‘the relevant expertise or creativity, irrespective of where they appear in the school staffing structure’ are empowered (Cheminais, 2015)

While this may require challenging a prevailing culture, the message is an important one for school leaders, especially this year. We need to make the best use of our expertise wherever it is to be found within our organisations, regardless of hierarchy.

This must not mean slipping back to an approach where TAs become informally responsible for children who have SEND. Specialist interventions do need to be guided by specialists with expert knowledge. But the focus of specialists must be to empower TAs and to recognise that they are likely to have different expert knowledge.

References:

Cheminais, R. (2009). Effective Multi-Agency Partnerships. London: Sage Publications

Cheminais, R. (2015). Handbook for SENCOs. London: Sage Publications

Coleman, A. (2011). Towards a Blended Model of Leadership for School-based Collaborations. Educational Management, Administration and Leadership, 39:3, pp 296 – 316

Education Endowment Foundation, (2020). The EEF guide to supporting school planning: A tiered approach to 2020 – 21

Education Endowment Foundation, 2020. Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools guidance report