Effective scaffolding

Scaffolding was put up on the side of my house just before the start of the pandemic, staying there for months while much of the country locked down (requiring daily reminders to my son not to climb up it). The scaffolding ended up being in place far longer than it should have been.

Likewise, in my Year 11 teaching last term, I found myself over-supporting a pupil with Developmental Language Disorder.

I provided an additional scaffold for extended writing tasks, without thinking enough about how to remove the support as and when it was no longer needed. While I was taking a completed writing frame to his desk, and assisting him like this throughout the year, I should have considered the steps towards independence, appropriate to his learning needs and to the progress he was making.

This might have meant giving him a partially completed writing frame, or asking him good questions so that he could complete it himself. Such an approach can increase the challenge for him and gives him the clear message that his need for additional support had reduced over time.

The point of scaffolding – whether on a house or in a classroom – is that it provides the support required, which is then removed when no longer needed. For teachers, how and when we remove our classroom scaffolds is a vital part of effective practice for pupils.

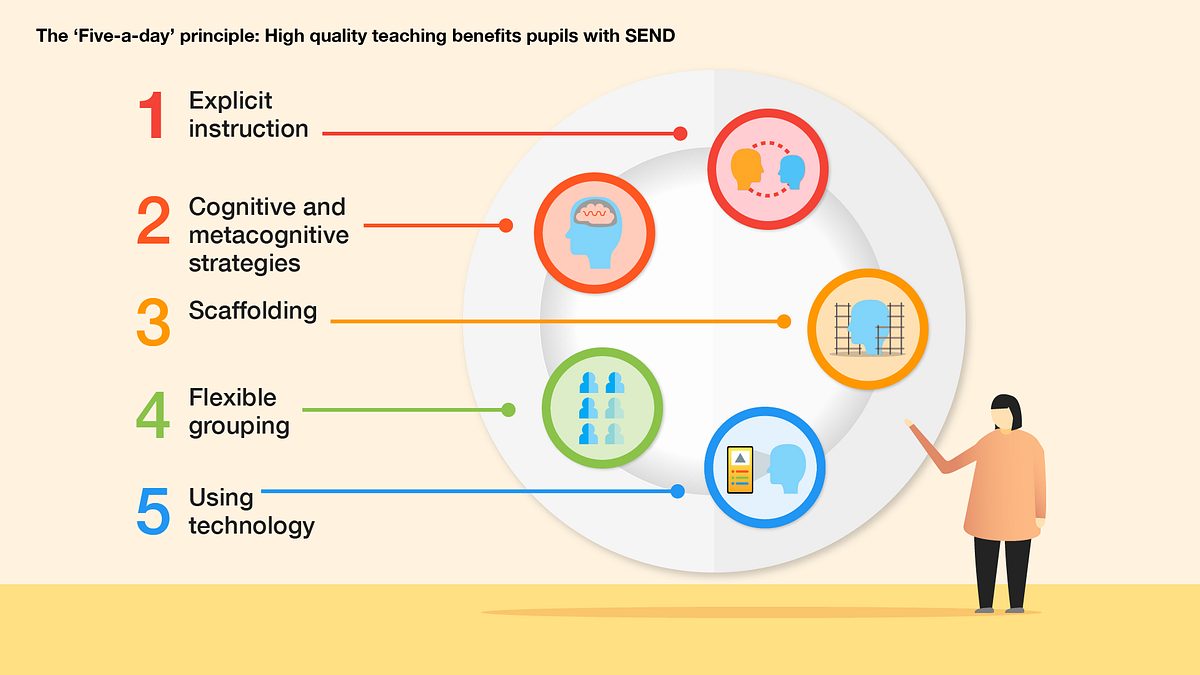

What does the EEF define as ‘scaffolding’?

The EEF defines scaffolding as ‘a metaphor for temporary support that is removed when it is no longer required’, providing ‘enough support so that pupils can successfully complete tasks that they could not yet do independently’.

Rather than requiring teachers to be creating different worksheets for pupils with different needs, scaffolding can be a term used to describe:

- A visual scaffold, such as a task planner.

- A verbal scaffold, such as a teacher correcting a misconception at a pupil’s desk.

- A written scaffold, such as a writing frame.

This scaffolding tool from the EEF can help teachers to consider what effective scaffolding looks like and what it might mean for them in their classroom. It can support teachers to consider when and how scaffolds might be implemented for everyone, becoming a fundamental part of high-quality teaching, rather than an add-on.

Teacher workload

With a shift to adaptive teaching within the Early Career Framework, notions of teachers planning three different lessons, each with their own resources, for pupils with different needs have rightly been challenged. This unnecessary burden on teacher workload can be harmful to teachers’ wellbeing and – at worst – can cap expectations of pupils.

Using appropriate scaffolds can work well as a key facet of ‘adaptive teaching’. Scaffolds can often be created live, or become embedded within planning rather than feeling like an ‘add-on’.

In terms of the impact on teacher workload, it is more manageable to think of scaffolding as a verbal reteach, or a visual provided at the whole-class level, rather than always requiring additional planning and resourcing.

Scaffolding is more than just a worksheet. It is already part of most teachers’ practice – or can be relatively easily added. In harnessing the full power of this strategy, we can consider the range of scaffolds available and ask ourselves questions around how we reduce them. With these tweaks, we can bring our adaptive teaching practice closer to the evidence around what works for all pupils, including those with SEND.