- Evidence consistently shows that educators can implement approaches that benefit young children’s literacy learning. The EEF’s Early Years Toolkit estimates that children who take part in early literacy approaches make, on average, four months’ additional progress.

- Using multiple approaches together could aid children’s literacy development as literacy approaches appear to be mutually reinforcing.

- Children’s early literacy is dependent on their oral language skills. Approaches for teaching early literacy should, therefore, be used in ways that build on approaches that support communication and language, which are fundamental to children’s literacy.

- While there is evidence that implementing these approaches could have a positive impact on children’s literacy outcomes, there are still some questions that are unanswered and so more research is needed.

Literacy describes a range of complex skills. It includes the word-level skills of both word reading and spelling and the text-level skills of reading comprehension and writing composition. The overall aim of these skills is for an author to effectively communicate their message and for a reader to understand it.

These literacy skills (word reading, spelling, reading comprehension, and writing composition) rely, to some extent, on the same underlying processes and are therefore linked. Learning to be a reader and writer relies on three broad underlying skills or areas of learning:

- speech, language, and communication skills;

- physical development, particularly fine motor skillsFine motor skills involve small muscles working with the brain and nervous system to control movements in areas such as the hands, fingers, lips, tongue and eyes.; and

- executive function skills, including working memoryWorking memory is an executive function that describes our ability to temporarily hold and manipulate information in our mind. It acts like a mental notepad that helps us complete tasks and solve problems. and speed of retrieval from memory.

The extent to which these processes are involved differs between aspects of reading and writing and at different points during literacy development. Educators working with early years children play a pivotal role in laying the foundations for literacy by facilitating the development of the skills above, helping children learn how to engage these processes so they work together and, in the latter part of the early years phase, teaching knowledge specifically for literacy (for example, letter-sounds and features of books).

Given literacy’s reliance on other areas of learning, we encourage educators also to engage with other sections of the Evidence Store to support children’s literacy development. Our Communication and Language section is already live, with sections on physical development, self-regulation, and executive function coming soon. Early literacy approaches may also be used to support children’s social and emotional development. You may be interested in the Personal, Social, and Emotional Development section of the Evidence Store where you’ll see that stories are often used during interactions to support development.

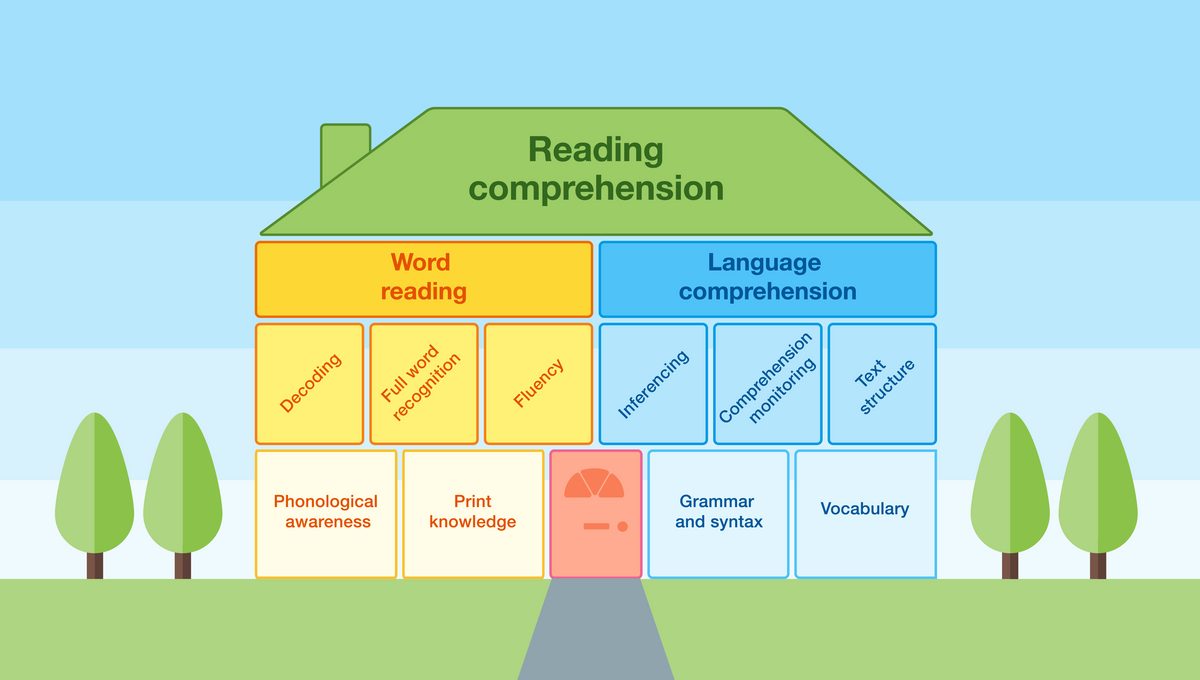

Early literacy is dependent on communication and language skills. The Reading House image below (adapted from Hogan, Bridges, Justice and Cain’s 2011 publication) is a helpful illustration of how oral language skills engage with literacy knowledge to enable reading comprehension. If we take a look at the right hand side of the house, the rooms that form the foundation of language comprehension are vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. You will find approaches within the Communication and Language section of the Evidence Store summarising what educators can do to support this learning.

Approaches that support communication and language are fundamental to supporting children’s early literacy. Children with language weaknesses may need more support with such skills to facilitate their literacy learning. Children with language weaknesses include those with a language impairment and may include children with English as an additional language or those from lower income families. Educators should use their own professional judgement and seek additional guidance when applying early literacy approaches to these groups of children.

Looking at the left hand side of the house, the rooms that form the foundation of word reading are phonological awareness and print knowledge. We recognise that phonological awareness and inferencing are oral language skills, however, we have chosen to cover approaches for how educators could support these outcomes in the early literacy section of the Evidence Store. This is because these skills need explicit support for the purpose of reading.

Approaches that educators can use to support the literacy development of children include:

- interactive reading: actions within the context of shared reading that encourage children to become an active participant in ‘reading’ the book;

- teaching sound discrimination: supporting children to identify sounds and notice similarities and differences between individual sounds and groups of sounds;

- teaching sound manipulation: supporting children to break down, combine, and change sounds;

- teaching sound-letter mapping: learning the written letters (graphemes) that go with particular letter-sounds (phonemes);

- interactive writing: the adult and child participate in the composing or writing process together; and

- teaching mark-making and letter formation: adults support children to use tools to make marks that represent their thoughts and ideas.

Approaches one to four are included in this current iteration of the Evidence Store. The page for each approach has two sections. The first is called ‘What Does the Evidence Say?’ In this section we share key messages about the approach from the research. The second is called ‘Approach in Action’ where we provide practical examples of how the approach could be implemented in settings. It draws on the experience and expertise of educators.

You will notice that interactive reading is an approach represented in both the Early Literacy and Communication and Language sections of the Evidence Store; this makes sense as the approach has been found to promote both outcomes. Please do engage with both sections as the evidence summaries and exemplification are different.

Approaches five and six do not yet have content as we are currently looking at the evidence base for these. Teaching mark-making and letter formation intersects with approaches for supporting children’s physical development; the EEF plans to review the evidence for physical development approaches before settling on which aspect to include within the literacy part of the evidence store.

Most studies underpinning the early literacy approaches in the Evidence Store involved research with four- and five-year-olds. A smaller number involved research with children aged three or six. Studies were included if a majority of children were aged six or under.

In addition to the evidence summaries, the Evidence Store also includes videos and written examples drawn from practice that aim to be relevant across the early years age group. The Evidence Store provides a summary of evidence about what is likely to be beneficial based on existing evidence — ‘best bets’ for what approaches might work. Your professional judgement and knowledge of the children in your settings is also needed to move from the information and examples to an evidence-informed decision about what could work best for children in your setting.

The evidence also revealed broader strategies to improve children’s literacy skills. These include:

- professional development for educators;

- additional small group or one to one support for children; and

- education technology (EdTech).

Most of the studies that look at the impact of educators’ practice on children’s literacy outcomes involve the educator receiving professional development or training in the approach. Professional development focused on language and literacy can have a positive effect on children’s literacy outcomes. It may be useful to review our Guide to Effective Professional Development in the Early Years and accompanying systematic review to consider key features of professional development that are associated with improved outcomes for children.

There is also evidence that additional targeted support — small-group or one to one — can help children develop their literacy skills and have a positive impact on their literacy outcomes.

Research indicates that educational technology (EdTech) can also positively impact literacy outcomes, especially when it aligns with the curriculum and is supported by good teaching. However, support provided directly by an adult rather than through EdTech alone may have a greater impact on phonological awareness and sound-letter mapping. Educators should prioritise ensuring children receive high quality interactions and use targeted support before considering EdTech as the approach to enhance their literacy teaching. The use of electronic storybooks and multimedia e‑books is explored in more detail within the Interactive Reading section of the Evidence Store.

The EEF’s Preparing for Literacy guidance report focused on children aged three to five with exemplification intended for a school audience. It drew largely on studies in the EEF’s Early Years Toolkit but also on two other EEF funded evidence reviews, one covering early language development (Law et al., 2017) and one on literacy development (Breadmore et al., 2019). It considered broader areas where there is evidence that certain behaviours and activities can make a difference to children’s early literacy, language, and communication skills. This includes the importance of effective parental engagement, using high quality assessment to ensure all children make good progress, and the value of targeted interventions when extra support is needed. This is different to the Evidence Store, which focuses specifically on approaches and practices that educators can use in face to face interactions with children using evidence and practice examples with children under six.