Findings from cognitive science can offer useful insights for teachers in every classroom. In the recent EEF commissioned review on Cognitive Science, one of the areas of interest for me were the insights on ‘working with schemas’.

So, what is a schema? Put simply, it describes the vital interconnected networks of background knowledge that prove so crucial for our pupils’ learning. As the review states, “working with schemas often involves developing ideas through processes of organization, comparison, or elaboration.” It may be the schema we intentionally develop about a topic in discussion, or the careful use of graphic organisers to compare ideas.

We all know that developing rich, connected schemas in the minds of our children is a sure-fire way to be able to create, develop and embed knowledge. Once one branch of a schema has been forged, it acts as arm which reaches out as a hook to welcome new knowledge.

Intentionally creating a schema can be compared to trekking through an overgrown forest. Teachers are the axe wielders who navigate the new learning and create the pathways. As we provide high quality instruction, these paths become clearer.

Sometimes, the insistent weeds begin to creep onto the pathways and children ‘forget’ the knowledge. Recognising and addressing this forgetting is crucial. It is the optimum time for teachers to deliberately retrieve that knowledge and cut down that weed through low-stakes quizzing – clearing the pathway even further.

It is important that as we build on prior knowledge, we avoid overloading pupils with tasks. They can only grapple with so much new information and their background knowledge is often underdeveloped.

As such, we understand that there will be a hinge moment in our lessons where we ask – do they understand what I have taught? We consider whether their schemas for a given topic are developed enough to ensure understanding. Dylan Wiliam promotes ‘hinge questions’ for this reason – offering a vital feedback opportunity to assess whether pupils are connecting up their knowledge to form understanding.

The key principles of hinge questions include:

- Ensure a response from every pupil (a quick check, rather than an extended discussion).

- Use plausible ‘distractors’ (wrong answers) and multiple correct responses to assess all children, so that they cannot simply guess a response.

- Ensure pupils’ responses enable the teacher to decide about their next teaching steps.

Knowing each pupil’s response enables the teacher to make a decision: do I continue clearing the path further ahead, or do I stop and take a few steps back? Subtle differences within the optional responses to hinge questions can ensure that the children are with you on this journey.

The use of multiple-choice questions can be criticised as inappropriate for complex tasks in subjects like English. However, we can attempt to understand these hinge points for more sophisticated material.

For example, in geography, a successful hinge question which allowed me to check whether children had embedded knowledge about the velocity of a river or still had misconceptions.

As explored in the EEF’s shorter summary resource to go with the Cognitive Science review, ‘concept mapping’ (see pages 31 to 34) is a strategy used to organise new knowledge and teachers presenting knowledge in a meaningful way creates an opportunity for children to create a schema.

In English lessons, children can think about the characters through a ‘concept map’. Finding out more about them in this structured way allows them to make predictions or summarise information about key characters. For example, when I teach ‘Alpha’, by Bessora, I will help pupils devise a concept map to shape the relationships between the family at the heart of the story. Simple ways to organise our pupils’ knowledge – building their schema – reduce the demandingness of reading complex texts.

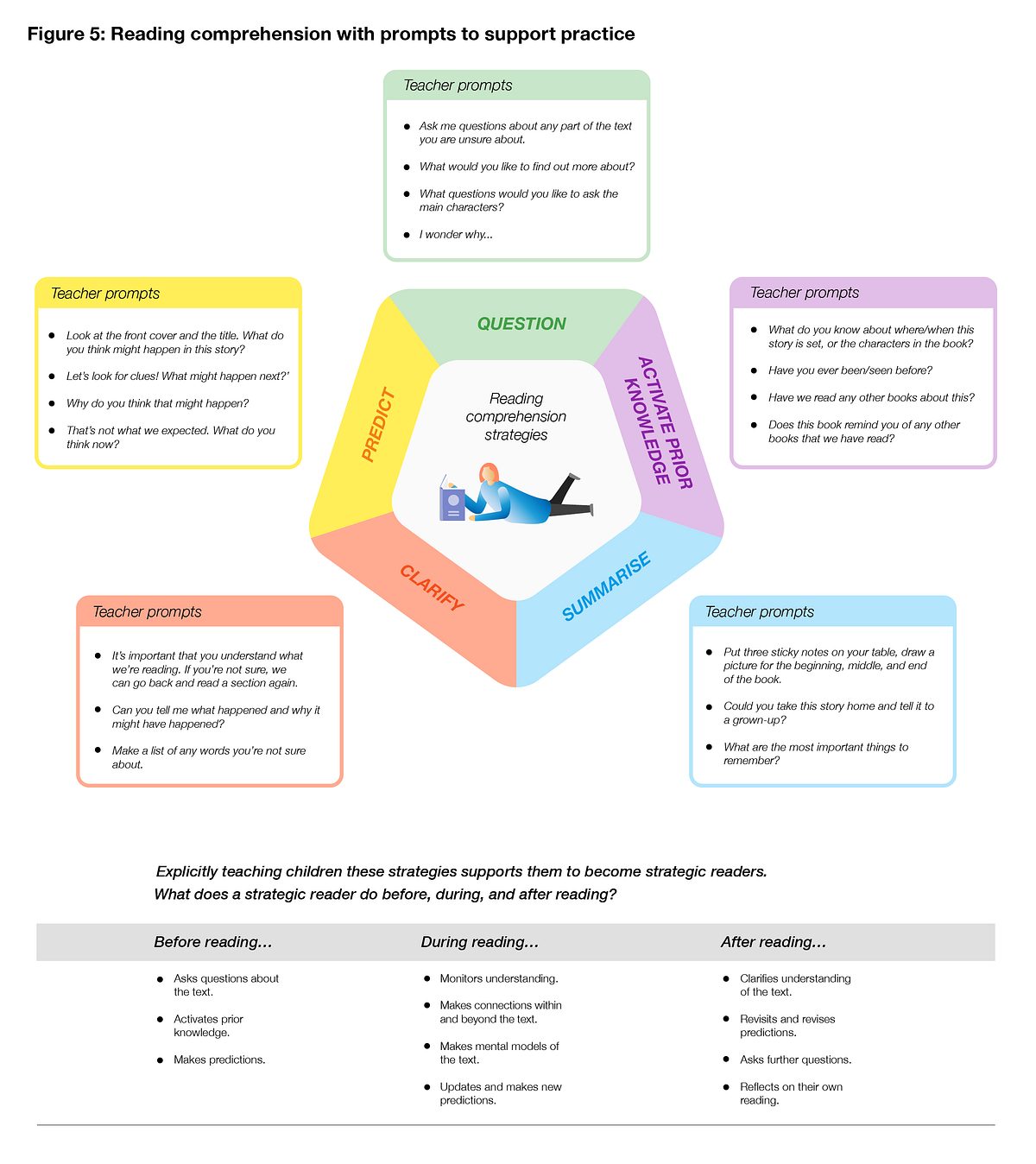

If they understand relationships between the characters beforehand, then we can maximise their focus on comprehending the text and its complex themes. Reading comprehension strategies, such as summarising (see recommendation 4 of the ‘Improve Literacy at Key Stage One’), allow the space for children to check whether they are understanding the material they are reading. Summarising portions of a text help once more to work with developing schemas for our novice pupils. It is another example of how teachers clear the way in the overgrown forest for our novice pupils.

All of these approaches – hinge questions, concept mapping, and reading comprehension strategies – ensure that children are walking their own pathways and are provided with their own axes to organise what they know and apply it with success. Working with schema is a concept from cognitive science that it is worth every teacher exploring.

Evidence and resources

Cognitive science approaches in the classroom

Podcast

New episode of ‘Evidence into Action’ – ‘Cognitive Science in the Classroom’

Guidance Reports